Max Wenner was a person who was referred to in a previous blog post, having fleetingly been mentioned in the book The Prince of Poachers.

That slight reference really engaged my interest and since then I have done a little internet research. By that I mean I have looked for the full story and, having failed to find one, have pulled together various references (from the links at the foot of this page), some of which are prime sources and others not, to piece together the story. The picture that emerges is a hazy, but intriguing one. It could perhaps form the basis of a film, certainly a book and undoubtedly a documentary for television. But that is not to trivialise, however, one man’s tragic demise.

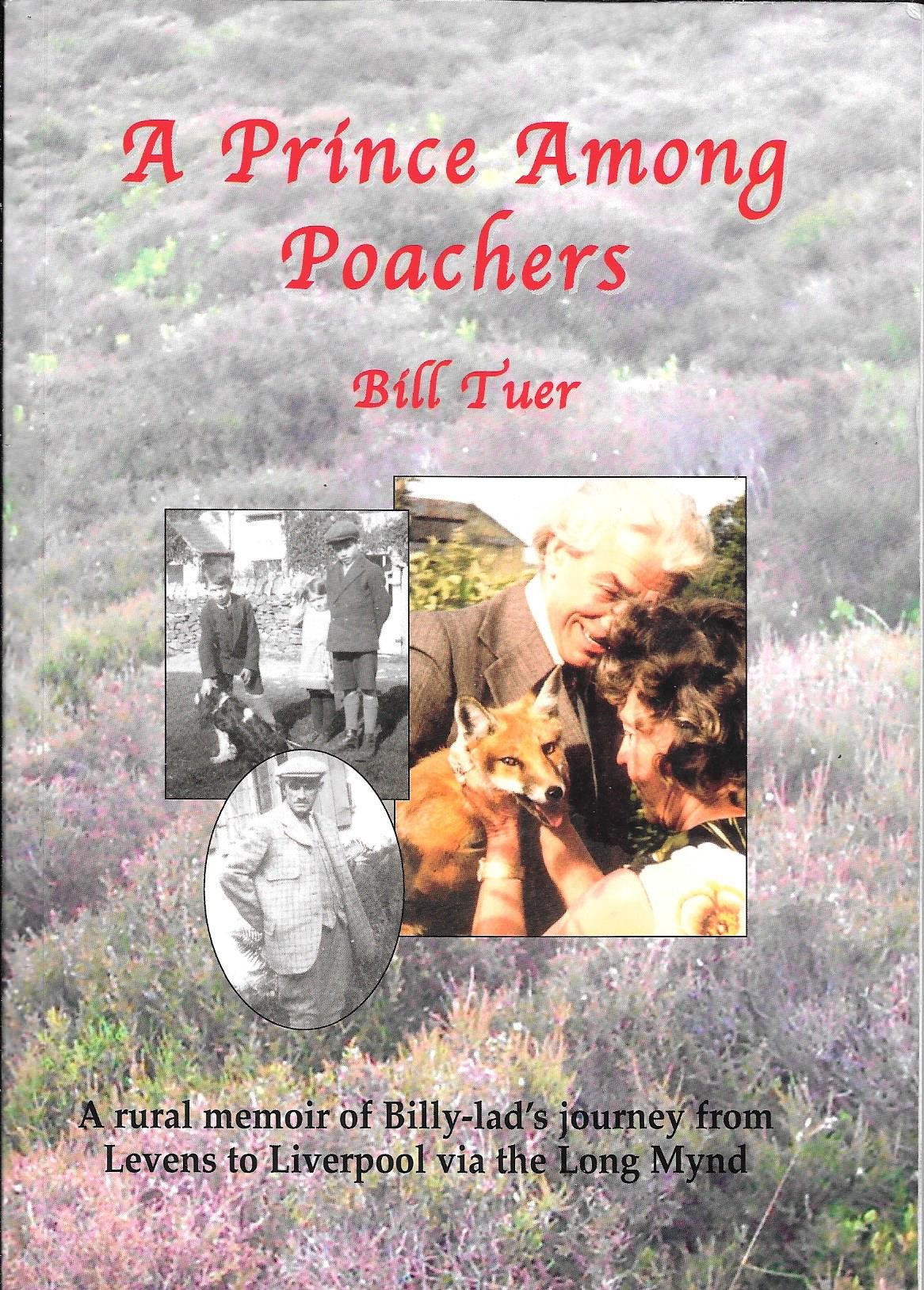

So let’s start with my own original datum point, the book excerpt. Quoting it in full, starting by talking of Long Mynd moor it says:

“I think it must be the ideal spot for a gliding club; there seemed to be very few windless days. A German gentleman, Max Wenner, was a leading light in this gliding idea there. He fell – or was he pushed? – out of a plane over the Channel. He was staying in a pub in Minsterly. Somehow Father was in on the search of his rooms. I remember seeing a gun in the shape and size of a fountain pen that fired a three-sided bullet.”

This is, my research has shown, is very much a mixture of vagueness and error – mostly the latter.

The man in question was an Englishman of Swiss extraction (not German) and very anti-gliding, which he felt disturbed the grouse on the Long Mynd moor shoot. He was co-owner of that shoot, which explains why the author’s father, one of the shoot’s gamekeepers, was present when the rooms were searched (or perhaps just cleared). Though mention of him having rooms at a pub is curious as Wenner lived fairly locally. And finally, his death was on the other side of the Channel and not above it.

Mr Max Victor Wenner was of Swiss descent from a family of wealthy textile manufacturers who had settled in England during the 19th century. Born around 1888, he was the son of Alfred Wenner and his wife Malvine (nee Egloff). Alfred had initially been married to Louise Egloff. They had three children together before she died aged just 25. He subsequently wed her older sister, having six more children.

Albert’s family wealth came from the textile industry and that is no doubt what drew him to the cotton capital of Manchester. He had premises in the city at Greenwood Street and seems to have diversified his business interests, and articles can be found where he is selling drilling machines and “an invention of improvements in fire bars and grates.”

The family lived in Earnscliffe Villa, a large house in Alderley Edge, Cheshire.

Albert died in 1911 at around 56 years of age. The following year, Max Wenner gives his address as Woodside, Trafford Road, Alderley Edge, though I don’t know if this is solely his home, or the whole family relocated following the patriarch’s death.

Malvine died in 1925 aged 77 by which time, or following which, Max had moved to Garthmeilio Hall, Langwm, Conwy, North Wales.

Max was keen on the outdoors, particularly birds and more generally shooting and fishing.

He was elected to the British Ornithologists Union in 1912 and appears in their publication “Ibis” and a number of other periodicals. For example a 1926 issue of The Field quotes him talking about stoats’ interest in the guts from rabbits he’d shot and there are a number of articles on birds carrying his name, including one from December 1933 on “Vipers Preying on Young Birds” – including photographs.

His brother Captain Alfred Emil Wenner was a British Army officer and the pair were photographed earlier that year on 14th July, by the River Thvera in Iceland, after they had caught 55 Salmon by lunchtime, with another 22 landed afterwards.

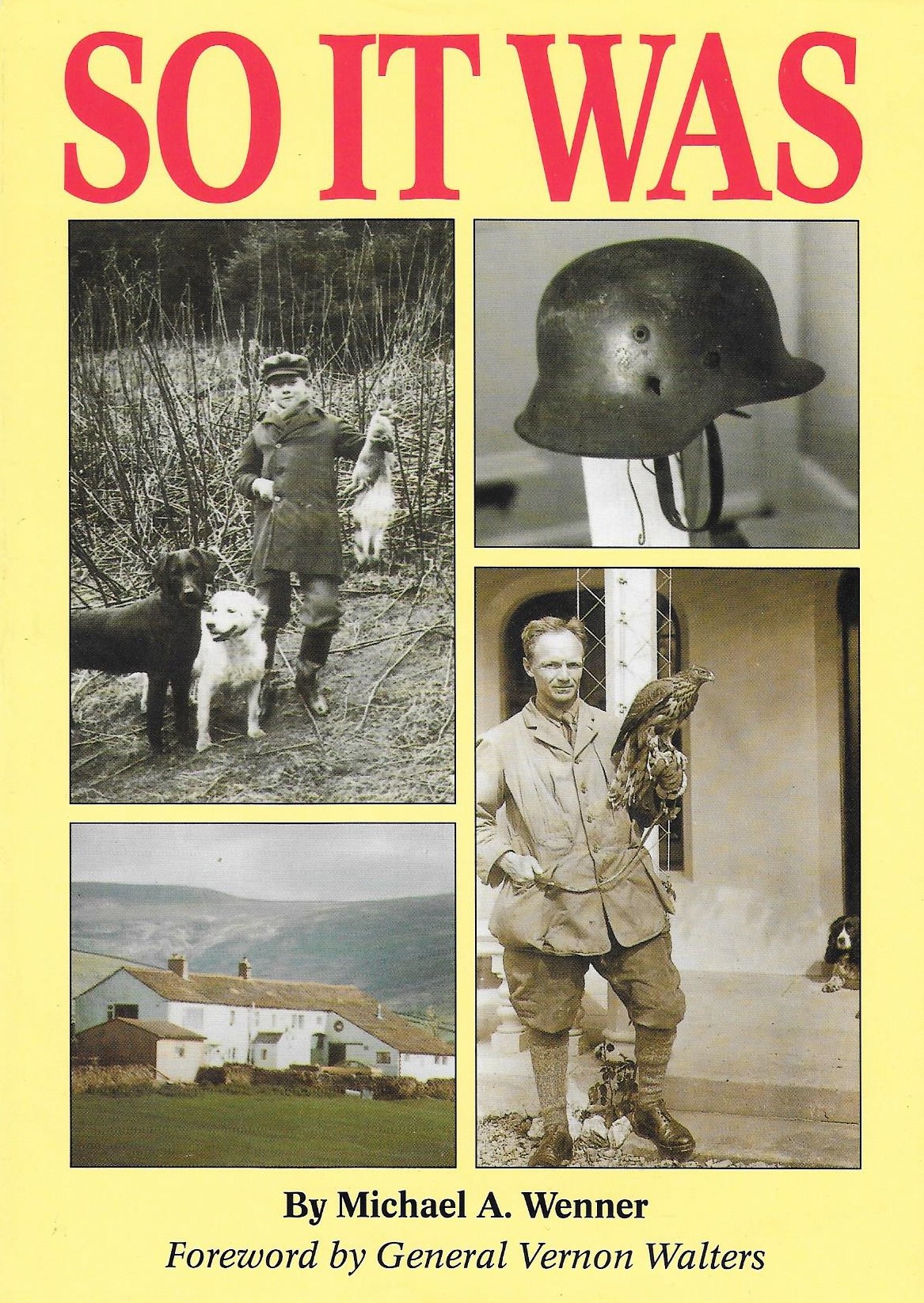

Much of this family biographical information comes from the WebPages of the State Archive of St Gallen in Switzerland, which also includes photographs of Earnscliffe Villa, Garthmeilio Hall and of Max and his wife. In one, which I think might be at Garthmeilio Hall judging by the balustrade in the background, he looks very much the countryman. Wearing a heavy jacket, plus-fours, thick socks and stout shoes, he stands before the camera with a hawk perched on his left hand.

By 1934 Max was living at Batchcott Hall. when he bought the manor of Church Stretton, to the east of Long Mynd moor. Manor here seems to be in the sense of a tract of land, rather than a manor house. He was one of three owners of Long Mynd, and it might be assumed that this ownership came with the manor. Batchcott is a hamlet to the north of the moor.

He owned 6,000 acres in all and spent a large sum improving the hall and building a bird sanctuary and lakes for trout fishing.

He’s also said to have put a lot of effort into developing shooting on the moor and so when gliding started there in the summer of 1934 he did not approve. Though It’s not clear whether that was due to thinking that the gliders themselves disturbed the birds, or because of the hoi-polloi, who came to watch the engineless planes, tramping across the land (it does seem to have been a spectator sport). Legal action followed, presumably initiated by Wenner and partners, with a four-day hearing closing on 15th March 1935 with Justice Crossman “effectively” banning flying gliders from Long Mynd, as it “interferes with grouse shooting”.

Wenner is described as “devoted” to his wife, Martha Alice Spinner, known as “Dollie”. She was about eight years his senior and aged around 58 passed away in July 1936.

He was in the habit of flying to Germany and Switzerland for winter sports.

On one of those winter sports trips in Switzerland, he befriended the 34 year-old Olga Buchenshultz. She was secretary to the Swedish Consul-General at the German town of Duren.

The friendship developed and they became engaged to be married in the second half of 1936.

Olga apparently had doubts whether a German woman should marry an Englishman, perhaps because of the European political situation, or was this to do with the 15 year age gap – probably not as that was not unusual at the time, I would suspect his recent bereavement.

Whatever the case during Wenner’s visit to Olga in Kupferdreh, a district in the south east of the German city of Essen on December 30 she promised to marry him. Wenner’s brothers and sisters it seems were aware and agreeable to this engagement.

On Monday 4th January 1937 Wenner started the journey back to England taking a Belgian airliner from Cologne to Brussels. Fellow passengers described him as seeming agitated and spending 20 minutes writing a single letter of many pages, which he put in his pocket and then left the compartment going to the rear of the plane.

The aircraft was flying at 3,000 above unbroken cloud over Limburg, when the other passengers heard a bang and felt the plane lurch. This was ascribed to the plane’s rear door slamming shut and they seem to have guessed what the reason for that was and a nurse was who was onboard fainted.

The man’s body was tragically found four days later on 8Th January, in a forest outside Genk, Belgium. It was apparently unblemished apart from “a scratched nose and buttons torn from his coat, there was no visible sign of injury”, apparently due to the trees slowing his fall. An unfinished letter to Olga was found in his pocket.

Belgian officials called his death a “mysterious accident” and it seems one of his brothers looked into matters speaking to Fraulein Buchenschultz.

Other passengers flew on in another plane to Croydon (Britain’s major international airport at the time) where they spoke to the press and the story was reported in newspapers as far away as Singapore and Australia.

Shortly before his death Max had made a will. This was perhaps sensible given his wife’s passing. I’m assuming here that she was a significant, if not his sole beneficiary. However, in light of his curious demise, one might view this differently, particularly as he left Olga Buchenshultz, £2,000 “in case anything should happen to me before our marriage.”

The will was proved in May 1937 and he left a large part of his estate, including Church Stretton manor and his share if the grouse moor to his friend and former agent William Humphrey, a renowned breeder of English Setters.

According to one reference I came across Max Wenner is said to have been ‘well connected in the highest political circles, both in England and Germany” and so it has been supposed that his unusual death had a “connection with espionage”. But I have found no prime source for this speculation.

As a true-life story, it does have the ring of an Agatha Christie novel.

Returning to the origins of my research, the mention of a fountain pen that fired bullets does make us in these times think of James Bond, but back in an era when the sword-stick was not uncommon, pen-guns were not necessarily the preserve of spies and spooks and this was a man who would have been au fait with many firearms.

The mention of Wenner having rooms in a pub at Minsterley is curious though, as it is not far from his home (about 32 miles by road) but is perhaps a mistake by an unreliable source.

All in all, it is an intriguing, but tragic tale.

There is a follow up piece to this post.

SOURCES

http://www.ukairfieldguide.net/airfields/Church-Stretton

http://www.ukairfieldguide.net/airfields/Long-Mynd

https://m.facebook.com/graysgundogs/posts/1797086413838175

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/salop/vol10/pp72-120

https://www.churchstretton.co.uk/

http://mvsetters.com/MrHumphrey.html

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_Mynd

https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v051n02/p0271-p0278.pdf

https://www.lax-a.net/good-old-times-in-iceland/

https://www.pestsmart.org.au/behaviour-of-stoats/

http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/singfreepressb19370204.2.87

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/58778222

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/47776628

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/11954611

http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19370106-1.2.41

https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/34404/page/3617/data.pdf

http://scope.staatsarchiv.sg.ch/detail.aspx?ID=114333

https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/search/results/1937-01-01/1937-12-31?basicsearch=max%20wenner%201937&exactsearch=false&retrievecountrycounts=false

https://prabook.com/web/michael.wenner/564292

http://scope.staatsarchiv.sg.ch/Detail.aspx?ID=114334

https://www.rootschat.com/forum/index.php?topic=444746.0

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1914.tb06642.x

https://archive.org/stream/britishbirds2319unse/britishbirds2319unse_djvu.txt

https://archive.org/stream/ibis_21914brit/ibis_21914brit_djvu.txt

https://archive.org/stream/britishbirds2219unse/britishbirds2219unse_djvu.txt

http://scope.staatsarchiv.sg.ch/Detail.aspx?ID=114211

http://scope.staatsarchiv.sg.ch/detail.aspx?ID=114197

https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/24001/page/3514/data.pdf

https://www2.cs.arizona.edu/patterns/weaving/articles/tm4_mach19.pdf